Do Wood Stove Changeout Programs Actually Work?

We recently came across a page on the British Columbia Lung Association website that touts the success of their long-running wood stove changeout program. The page claimed that the program, which began in 2008, has “reduced particulate matter emissions by over 400 tonnes per year.”

This claim struck us—to put it politely—as surprising, so we wrote to the Lung Association asking them for details. They never replied.

What made us so skeptical of this claim? For one thing, an in-depth evaluation of the British Columbia wood stove exchange program published in 2014 noted that 6 years after the program began, “…there has not yet been a clear reduction in fine particulate matter pollution coming from residential wood stoves in BC.” Another study that compared pollution levels in homes before and after the program concluded, “There was not a consistent relationship between stove technology and outdoor or indoor air quality indoor concentrations of PM2.5.”

Perhaps things had turned around since those studies were published? Apparently not, since the BC Lung Association’s own 2018 “State of the Air” report shows that there were no significant decreases in PM2.5 (particulate matter smaller than 2.5 microns in diameter) from 2008 to 2017.

One might reasonably ask: What’s going on here?

Our educated guess is that the BC Lung Association’s claimed reduction in PM2.5 of 400 tons per year is likely a calculated reduction based on taking the certification values of EPA wood stoves and multiplying them by the number of wood stoves that have been changed out through the program.

This is like claiming that you lost 20 pounds based on counting how many calories you ate last month rather than actually weighing yourself.

So why wasn’t the program as effective in reducing wood smoke pollution as it was projected to be? The answer is simple: EPA-certified wood stoves do not perform as well in the real world as they do under the laboratory test conditions that are used to produce their certification values. Indeed, it is widely acknowledged by the EPA—and even by the hearth products industry—that wood stove certification values do not correlate well with the in-home performance of wood stoves.

One study found that certified wood stoves operated by homeowners in their own homes produced up to 30 times more particle pollution than their certification value.

The Trouble with EPA Certified Wood Stoves

There are many reasons why EPA certified wood stoves perform differently in the real world than they do in the test lab. In the real world, people burn wood that isn’t perfectly dried. They “damper down” their wood stove overnight or when their home gets too warm. They overfill the firebox with logs. In reality, it takes a lot of work to burn wood properly—and the end user doesn’t have a lot of incentive for doing so, since the majority of the pollution they create disappears up their chimney and out into the neighborhood.

While EPA certified wood stoves have been aggressively promoted as a panacea, in reality an improperly operated EPA certified wood stove emits more pollution than a properly operated conventional wood stove. Even if EPA certified wood stoves performed as well in real life as their lab certification values would suggest, a single stove would emit more fine particle pollution than hundreds of homes using a gas furnace (electric heat pumps produce almost no particle pollution).

Largely due to industry influence, the EPA test method is gamed to present an unrealistically optimistic picture of wood stove performance. For example, rather than logs, it uses kiln dried lumber that is arranged in a crib formation and specifically excludes the massive amount of pollution that is created when the wood stove is started up.

Wood Stove Changeout Programs: Disappointing Results

The sad reality is that the effectiveness of wood stove changeout programs that incentivize the sales of new EPA certified wood stoves has never been adequately demonstrated in real world studies. Yet in spite of this, due to pervasive industry influence, wood stove changeout programs have become the de facto response by air quality regulators to the problem of wood smoke pollution.

The Hearth, Patio and Barbecue Association is the main lobbying organization for the wood stove industry. On a website they host dedicated to wood stove changeout programs, there is a section dedicated to “success stories.” While these success stories include details about capturing “congressional earmarks” to fund new wood stove sales, they curiously do not include data showing actual air quality improvements (other than, once again, calculated estimates).

The one program that is constantly cited in favor of wood stove changeout programs was subsidized by the wood stove industry and took place in Libby, Montana. From 2005–2007, 95% of all the non-certified wood stoves in the community were replaced. In the year following the changeout, PM2.5 levels fell by 27%. But this was less than half the reduction that would be expected if the new, certified stoves actually emitted 70% less particulates than the old stoves, a figure cited by the EPA.

Notably, the relative contribution of wood smoke to PM2.5 levels was unchanged following the changeout, raising the question of whether the PM2.5 reduction was due to changes in wood stove technology or to another factor, such as newer cars on the road. Moreover, a study of air quality at two schools found that “…the changeout did not result in a measurable improvement on school indoor air quality.” When researchers looked at air quality inside houses following the changeout, 5 of 21 houses actually showed increased PM2.5 levels.

A Better Solution to Wood Smoke Pollution

If changeout programs that subsidize sales of new EPA certified wood stoves don’t work, what does?

Somewhat ironically, the 2014 report on the British Columbia program showed the way forward, stating: “For many communities, the elimination of wood burning for heating may be the desired path to reduce exposure to pollutants.” In other words, if you want to eliminate wood smoke pollution, don’t encourage or subsidize the use of new wood stoves. Instead, subsidize only cleaner heating devices, such as electric mini-split heat pumps or gas heaters.

A changeout program in Launceston, Australia attempted to do just that, offering incentives to encourage homes that were heating with wood to switch to electric heat. Even though only half of the homes that were using wood heat converted to electric heating, particle pollution levels fell by 40%.

Despite the evidence that the British Columbia wood stove exchange program has not reduced particulate matter pollution from wood smoke, the 2014 report on the British Columbia wood stove exchange program states that “…the program has been very successful.” If PM2.5 levels haven’t dropped, how is success measured? Apparently by the number of stoves that are exchanged, even if air quality isn’t improved. This might be a win for the wood stove industry, but it isn’t a win for the residents of British Columbia who must live with the harmful effects of wood smoke pollution.

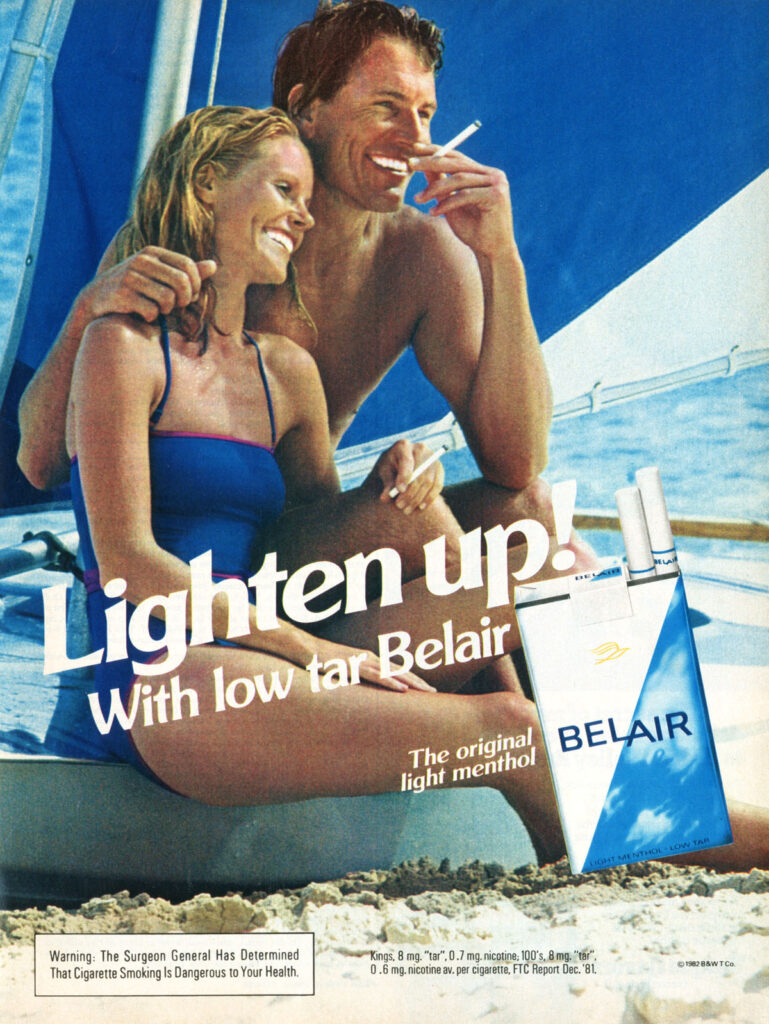

It’s not difficult to see why the wood stove changeout scheme rolls on: it gives regulators an easy way out by allowing people to continue burning wood. In reality, however, the idea makes as much sense as using public funds to subsidize light cigarettes for tobacco users instead of encouraging them to quit smoking.

(Photo: Kim Nilsson)

Image: U.S. EPA

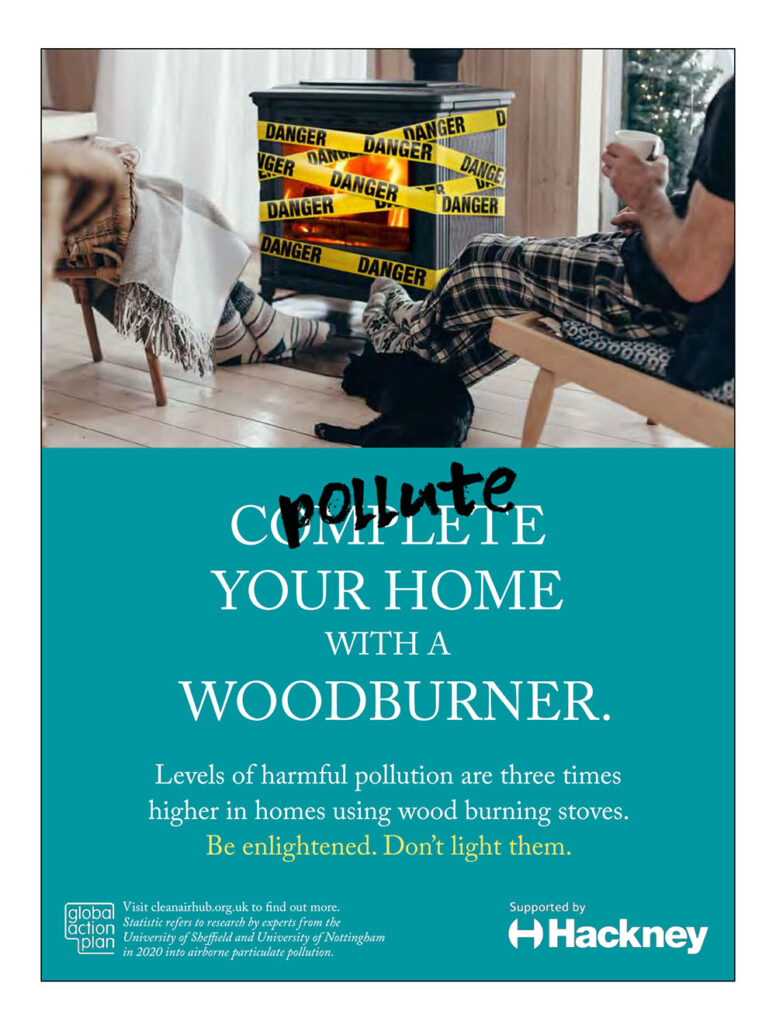

Image: U.S. EPA